Author: Phil Hyde

Introduction

On the 30th May 1979, a friend and I had travelled to Cley in Norfolk to try and see an adult Rose-coloured Starling Pastor roseus but the bird had gone. Later, as we walked rather disconsolately along the famous East Bank, two Norfolk birders shouted “Little Egret” and a fine adult flew past us on to Cley marshes, my first British record. The British Birds Rarities Committee (BBRC) subsequently accepted the record1. Thereafter, the species began to increase dramatically in the UK and 1990 was the last year in which it featured in the annual BBRC report, when there were 113 records2. This short report looks at the species’ status in Lincolnshire.

Little Egret Egretta garzetta Adult and juvenile North Cotes June 2015 © Colin Smale

Little Egrets in Lincolnshire in the 20th century

In the first treatise on the birds of Lincolnshire written by Smith and Cornwallis3 in 1955, the species is not even mentioned. A later update by Lorand and Atkin4 published in 1989 summarised the species status as “a rare vagrant recorded with certainty only during recent years”. The first acceptable record for the county was of a bird at Frampton marshes on 23rd July 1966, somehow a very suitable occurrence given the prominence that site now has within the county. Spring influxes of this species and other southern herons to the UK occurred in 1970 and 1973, resulting in six county records. Lorand and Atkin finish by stating that there have been at least five more records since, with one bird over-wintering on the Wash in 1987/88. The likely origin of these birds was hinted at when a Dutch-ringed bird was found dead at the River Welland mouth in September 1979, having been ringed as a nestling two months earlier.

In the wider context, Fraser et al. (1997)5 reported that during 1958-88 the average number of Little Egrets in Britain was fewer than 15 per year with most in spring. However, in 1989 this pattern changed abruptly (when coincidentally there was an over-wintering individual in Lincolnshire) when there was a dramatic autumn influx into Britain and Ireland from mid-July onwards6. The August peak for the southwest of England was more than 320 birds, with a slightly later peak (in September) in Dorset, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight reaching nearly 350. Lower August or September peaks were just under 100 (in East and West Sussex and Kent) and 50 (Wales, Avon and Somerset). The influx was much more modest in the midland and eastern counties and the 1989 Lincolnshire Bird Report7 noted just a single individual on the Wash into November! The origin of the influx was theorised as being northwest France, where hundreds have wintered from the early 1980s.

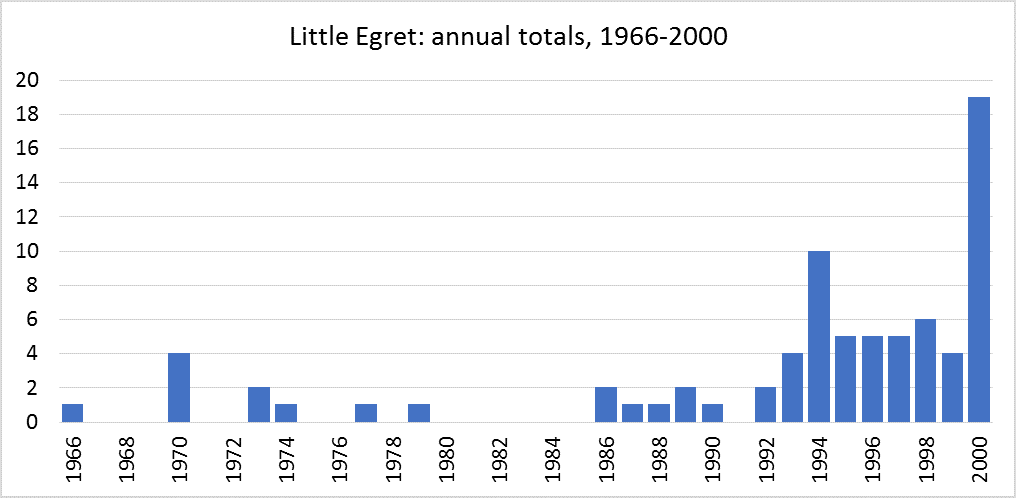

The numbers of Little Egrets present annually between 1966 and 2000 are shown in Figure 1. Data have been taken from the LBC archive (1996-2000) and crosschecked against BBRC reports (up to and including 1990). Between 1966 and 1992, the species remained a true rarity and the 1992 LBC Report noted that the two birds reported in that year were just the county’s 17th and 18th records. Even then, 1994 was the only year when double figures were reported (10) leading up to the end of the millennium when there were 19.

Figure 1: Little Egret Egretta garzetta numbers present in Lincolnshire during 1966-2000.

Note that during 1993-2000, the numbers are best estimates where multiple site occurrences had been reported.

Little Egrets in Lincolnshire and United Kingdom in the 21st century

(a) Total population

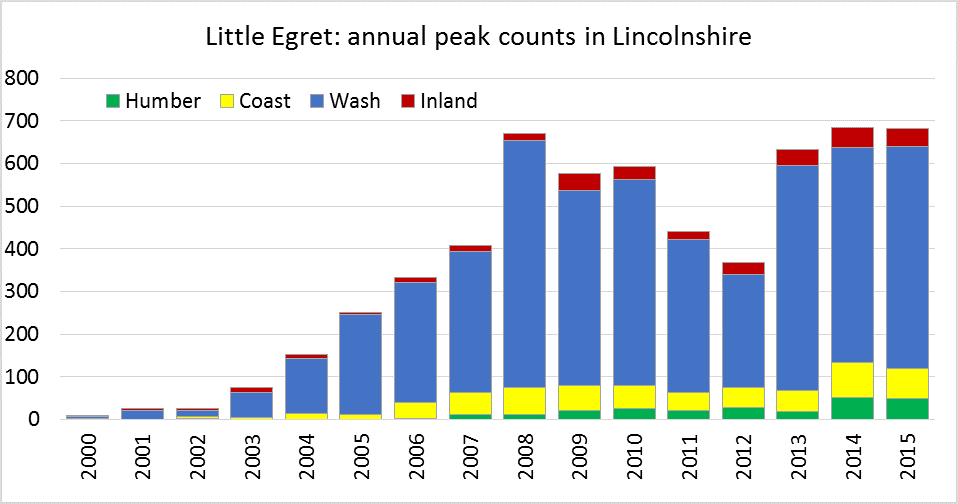

Little Egret counts in Lincolnshire submitted to the Lincolnshire Bird Club (LBC) and to the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) Wetland Bird Survey (WeBS) show an almost exponential increase in numbers from the turn of the millennium (Figure 2). Data have been analysed as follows. Peak monthly counts were identified in each of 26 sections of the county (two on the Humber, two on the coast, 15 on The Wash based on WeBS sectors, and seven inland). Those peaks were then summed to give monthly totals for the four areas (Humber, coast, Wash, inland). In any year, peak monthly totals for different areas may not occur in the same month, and there may be small biases due to duplication or poor coverage, but these factors are unlikely to have affected the displayed trends or estimated population sizes significantly.

The trend mirrors the establishment of Little Egrets as a breeding bird in the county (see below) but will also reflect the species northwards spread in the UK. The Wash has been by far the most important site during this period, with the northerly coastal sites and the Humber becoming significant from 2006 onwards. Inland sites also start to figure from that year. Numbers peaked in 2008 but subsequently suffered reversals due to several prolonged spells of freezing weather, not conducive to the survival of fish-eating birds, notably in 2010/11. There was a rapid recovery by 2013 but it remains to be seen whether the county total will continue to increase.

Figure 2: Annual peak counts for Little Egret Egretta garzetta 2000-2015.

These represent the highest monthly total for each area in each year.

(b) Seasonal pattern of abundance in Little Egret numbers

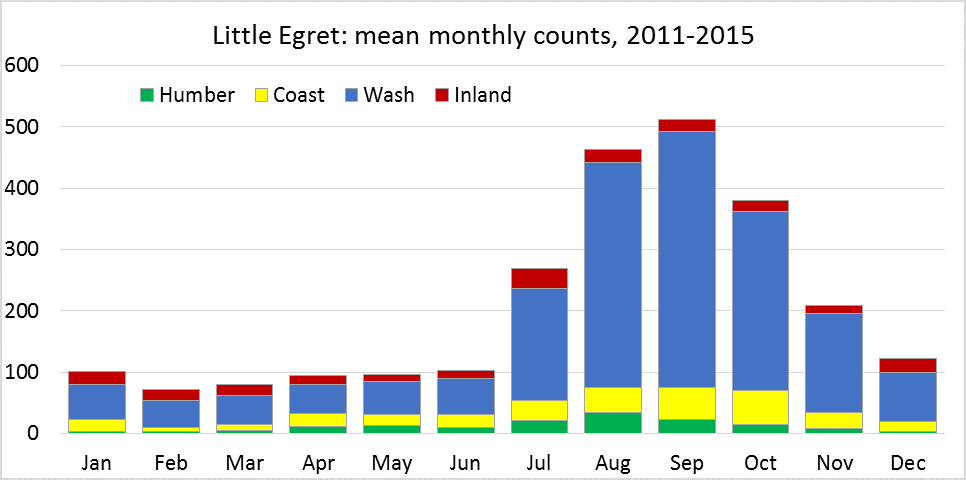

As would be expected as newly fledged youngsters are added to the population maximum numbers occur in the autumn starting in July and peaking in September (Figure 3). The highest numbers are seen on The Wash and on the coast and on the other estuary, the Humber. The totals will both reflect post-breeding increases locally bred and immigration from elsewhere - birds from Norfolk and Nottinghamshire have been observed in Lincolnshire. Post-juvenile dispersal in many species is a well-known phenomenon and birds ringed as nestlings (pulli) in Lincolnshire have been sighted as far afield as Aberdeenshire, Somerset, the Channel Islands and north-central France in the autumn months (see section (c) below).

Figure 3: Seasonal pattern of abundance for Little Egret Egretta garzetta 2000-2015.

For each area, the peak monthly total, averaged for the five years, is shown for each month.

Little Egret Egretta garzetta Freiston Shore Sep 13th 2015 © Steve Keighley

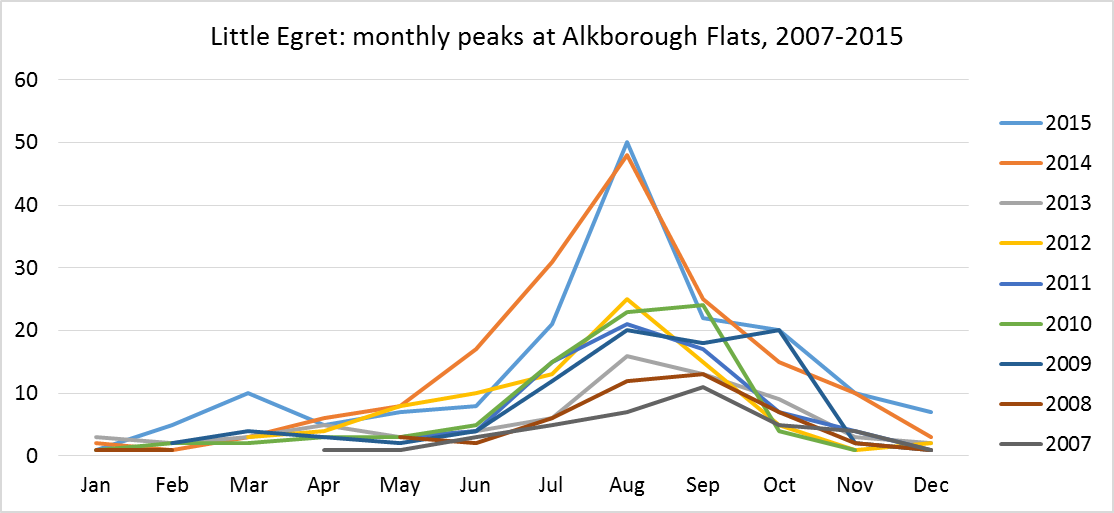

Data for one Humber site, Alkborough Flats, 2007-2015 is also shown in Figure 4, as an example of seasonal variation at a single coastal site. Little Egrets appeared later at this site, reflecting its position on the more northerly Humber estuary, but the autumn increase is again very apparent. Another small difference is that the autumn peak tends to be in August in contrast to the September peak for the county as a whole.

Figure 4: Little Egret Egretta garzetta monthly count data for Alkborough Flats, 2007-2015.

A late autumn and winter decrease in numbers is also clearly shown at both Alkborough and across the county. It is not known whether this reflects mortality, or movement away from the county into some of the larger concentrations seen further south in England. The UK wintering population is the most northerly in the world and high mortality has been documented in Brittany in the winters of 1984/5, 1986/7 and 1996/78, and is assumed to have been the cause of the declines in Lincolnshire in 2010-2012.

(c) Breeding status of Little Egrets in the United Kingdom and Lincolnshire

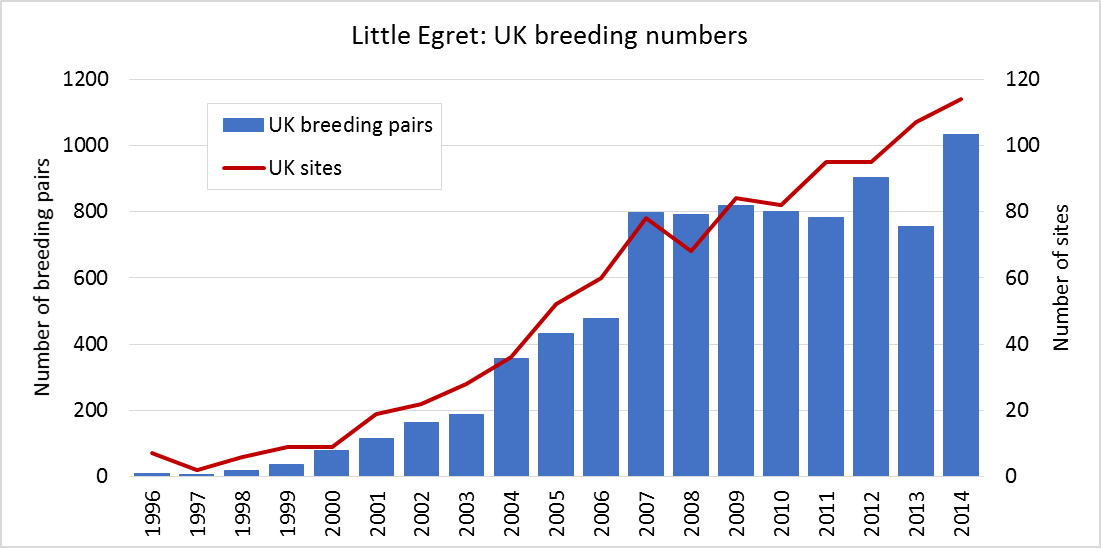

The first breeding of this species in Britain was confirmed in 1996, as had been well forecast, when a pair successfully reared three young on Brownsea Island in Dorset8. Although successful breeding was known to have taken place only at this locality, probable breeding attempts also occurred at a minimum of six others. Notable milestones after 1996 included a two-fold increase between 2003 and 2005; more than 800 confirmed and probable breeding pairs in 2009; more than 100 sites reporting confirmed or probable breeding in 2013; more than 1,000 breeding pairs in 2014 (the latest RBBP report) 9. Figure 5 shows the trend in the UK population.

Figure 5: Numbers of breeding pairs of Little Egrets Egretta garzetta in the UK, 1996-2013.

Note that “breeding pairs” is the total of confirmed and probable breeders. Data from the UK Rare Breeding Birds Panel reports, www.rbbp.org.uk

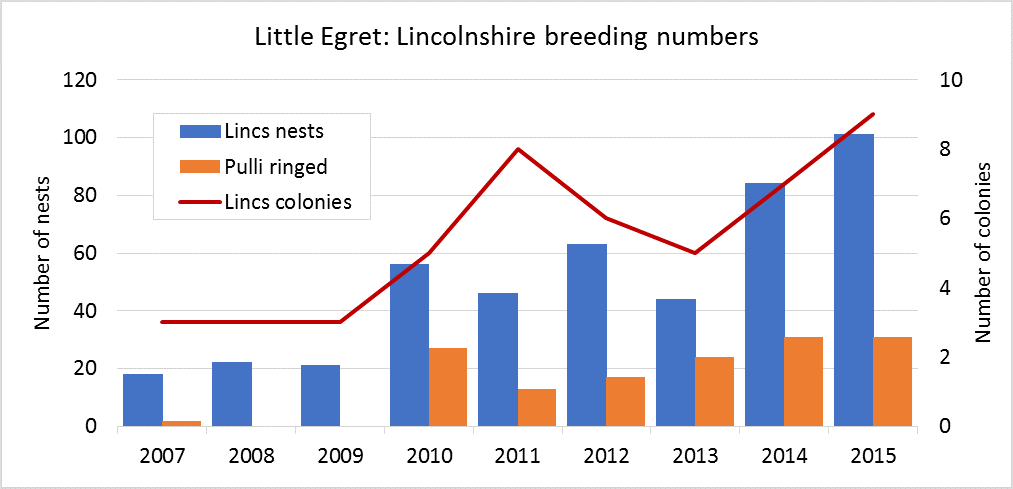

Confirmed breeding in Lincolnshire didn’t occur until 2007 when 16-18 pairs were reported from three localities following signs of breeding behaviour in every year from 2003 onwards10. Numbers of breeding pairs and sites with breeding attempts have increased rapidly since then, as shown in Figure 6, with at least 101 pairs at 9 sites in 2015 (see p. xx of this report). Figure 6 also shows the numbers of nestlings ringed in the county each year; note that these totals reflect ringing effort and do not represent the number of young produced.

Figure 6: Numbers of breeding pairs of Little Egrets Egretta garzetta in Lincolnshire, 2007- 2015.

Data from the UK Rare Breeding Birds Panel, www.rbbp.org.uk and Lincolnshire Bird Reports 2007-2015. Totals include confirmed and probably occupied nests.

Since the first confirmed breeding in Lincolnshire in 2007, 145 pulli have been ringed with both BTO metal rings and colour rings; maxima of 31 were ringed in both 2014 and 2015. Colour-ringed Lincolnshire birds have been observed alive in the field as far north as the Ythan Estuary, Aberdeenshire (445km NNW, Sep 2014), and as far south as Somerset (336km SW, Oct 2013); the Channel Islands (498kn SSW, Apr & Nov 2012); Loiret, France (561km SSE, Oct 2009) 11. The BTO longevity record for Little Egret is nine years and six months; that for Lincolnshire to date is six years and nine months11.

Unsurprisingly, the county breeding data mirror that of the rest of the UK with the trend continuing strongly upwards12. In the context of some other UK breeding species, Little Egret is bucking the trend of some widespread decreases13. It’s addition to the county avifauna and its establishment as a breeding species is a welcome event. Indeed, herons and their allies in general (Spoonbill, Glossy Ibis, Great Bittern) are also thriving at present. For example, two pairs of Great White Egret Ardea alba, first bred in the UK in 2012 (and may soon emulate Little Egrets). This followed a large increase in the wintering populations of Great White Egrets in the UK (records in 6% of 10-km squares in Britain in Bird Atlas 2007–11)10 and in Europe where it formerly wintered in small numbers or only occasionally, with flocks of several hundred individuals reported from some countries14.

Habitat usage by Little Egrets: feeding, roosting and breeding

In Lincolnshire, Little Egrets typically feed in a wide variety of habitat: open or sparsely vegetated shallow to very shallow water, both inland and coastal, including the banks of freshwater rivers and streams, shallow lakes, pools, lagoons, flooded meadows, freshwater ditches draining agricultural land, and open areas in marshes (mostly with Phragmites), and coastal mud flats.

Their choice of prey in these areas is quite catholic and they are swift to take advantage of local prey abundance. In Lincolnshire freshwater waterways of all kinds, personal observations have revealed that they favour small fish such as Three-spined Stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus and fry of species such as Common Roach Rutilus rutilus, and Rudd Scardinius erythrophthalmus. In saline lagoons and creeks, Brown Shrimp Crangon crangon, and Green Shore Crab Carcinus maenas are commonly taken. Familiar references such as Handbook of the Birds of the World15 give an exhaustive list of recorded prey species.

Roosting Little Egrets commonly choose somewhere close to their feeding grounds. In Lincolnshire this is primarily saltmarshes behind the shoreline, drainage ditches and tidal mudflats, copses and hedges. A copse largely of Sycamore Acer pseudoplatanus, is regularly used on the Wash at the Witham mouth, and Hawthorn Crataegus monogyna hedges at Gibraltar Point.

The habitat in which Little Egrets in the county choose to breed often involves co-habitation with Grey Herons Ardea cinerea. The colonies are most often sited in stands of conifer, including Larch Larix decidua, Scots Pine Pinus sylvestris and Norway Spruce Picea abies, but also in mixed deciduous and coniferous plantations in coastal shelter belts and copses. At one inland gravel pit site, thick Willow/Sallow scrub Salix spp is also used. Choice of host tree thus seems to be opportunistic, and may or may not involve a pre-existing heronry.

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the help received from Andrew Henderson and Andrew Chick in the analysis of the large amount of Little Egret data held in the LBC archive and in the preparation of the charts. In addition, grateful thanks to Neil Calbrade, WeBS Research Ecologist at the BTO, for extracting the Little Egret data for the Lincolnshire Wash sites.

References

- Rogers M.J and the Rarities Committee (1981) Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 1980. British Birds 74 (11): 453-495.

- Rogers M.J and the Rarities Committee (1991) Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 1990. British Birds 84 (11): 453-505.

- Smith A.E. and R.K. Cornwallis (1955) The Birds of Lincolnshire. Lincolnshire Natural History Brochure No. 2, published by the Lincolnshire Naturalists’ Union.

- Lorand S. and K. Atkin (1989) The Birds of Lincolnshire & South Humberside. Leading Edge Press and Publishing, N Yorkshire, UK.

- Fraser P.A., Lansdown P.G. and Rogers M.J. (1997) Report on scarce migrant birds in Britain in 1995. British Birds 90(10): 413-439.

- Combridge P. and Parr C. (1992) Influx of Little Egrets in Britain and Ireland in 1989. British Birds 85(1): 16-21.

- Lincolnshire Bird Club (1989) Lincolnshire Bird Report 1989 including the Gibraltar Point Observatory Report.

- Lock L. and Cook K. (1998) The Little Egret in Britain: a successful colonist. British Birds 91(7): 273-280.

- Lincolnshire Bird Club (2013) Lincolnshire Rare & Scarce Bird Report 2003-2007. Cupit Print, Horncastle, UK.

- RBBP - the secure information archive on the UK's rare breeding birds: rbbp.org.uk

- BTO On-line ringing reports: www.bto.org/volunteer-surveys/ringing/publications/online-ringing-reports

- Holling M. and the Rare Breeding Birds Panel. (2016) Rare breeding birds in the United Kingdom in 2014. British Birds 109 (9): 491-545.

- The Breeding Bird Survey 2015: The population trends of the UK’s breeding birds. BTO Research Report

- Ławicki Ł. (2014) The Great White Egret in Europe: population increase and range expansion since 1980. British Birds 107 (1): 8-25.

- del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.) (2017) Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/ on 5 February 2017).